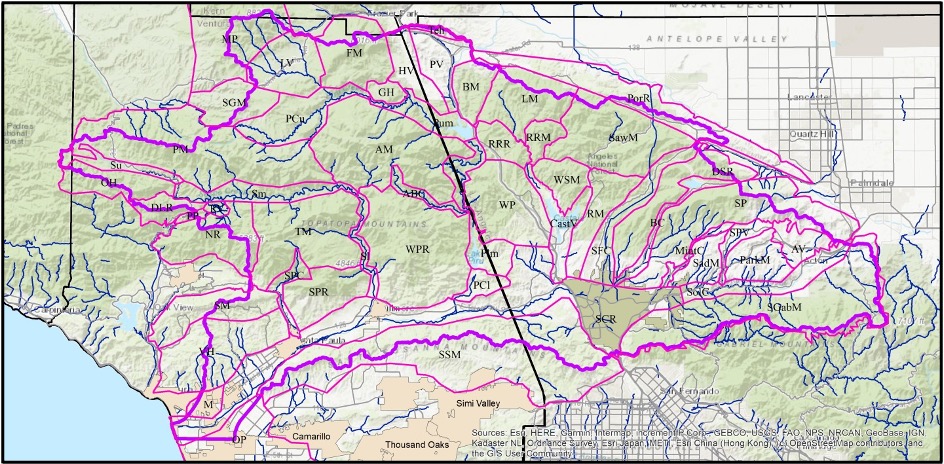

The Santa Clara (Utom) River watershed is located within northeastern Ventura County and northwestern Los Angeles County, with small areas of southern Kern and eastern Santa Barbara Counties included. The watershed encompasses2,023,358 acres (818,842 hectares). It ranges in elevation from sea level at the mouth of the Santa Clara River to 8,831 feet at the summit of Mount Piños on the Ventura-Kern County line. Utom is the Chumash name for the Santa Clara River. The bounds of the watershed are delineated on Figure 1, General Location Map of the Santa Clara River Watershed.

The watershed was divided into a total of fifty-four (54) bioregions based primarily on logical geographic features, such as valleys, canyons, plains, hills, ridges, and mountains, with the boundaries of the bioregions illustrated on Figure 2, Map of Floristic Bioregions of the Utom (Santa Clara) River Watershed. Names for each bioregion were assigned based on the most prominent geographic feature of that delineated area.

The California Native Plant Society (CNPS) is the Utom River Conservation Fund partner that focuses on the botanical resources of the watershed.

Figure 1. General Location Map of Utom River Watershed and Floristic Bioregions

There are fifty-four (54) bioregions within/making up the Santa Clara River Watershed. The name and acronym used on the map, landform, size, and county(ies) of each watershed bioregion is provided in the table below.

| Bioregion | Landform | Size | County |

| Acton Valley (AV) | Valley | 13,830 acres/5,597 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Agua Blanca Creek (ABC) | Canyon | 7,491 acres/3,031 hectares | Ventura |

| Alamo Mountain (AM) | Mountain | 89,090 acres/36,054 hectares | Ventura & Los Angeles |

| Bald Mountain (BM) | Mountain | 17,927 acres/7,255 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Bouquet Canyon (BC) | Canyon | 11,470 acres/4,642 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Castaic Valley (CV) | Valley | 20,673 acres/8,366 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Del Sur Ridge (DSR) | Mountain | 40,749 acres/16,491 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Dry Lakes Ridge (DLR) | Mountain | 12,440 acres/5,034 hectares | Ventura |

| Frazier Mountain (FM) | Mountain | 40,005 acres/16,190 hectares | Ventura |

| Gold Hill (GH) | Mountain | 6,196 acres/2,508 hectares | Ventura |

| Hungry Valley (HV) | Valley | 20,029 acres/8,106 hectares | Ventura & Los Angeles |

| Liebre Mountain (LM) | Mountain | 39,760 acres/16,091 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Lockwood Valley (LV) | Valley | 33,203 acres/13,437 hectares | Ventura |

| Lower Piru Creek (PCl) | Canyon | 8,592 acres/3,477 hectares | Ventura |

| Lower Sespe Creek (Sl) | Canyon | 8,070 acres/3,266 hectares | Ventura |

| Middle Lower Piru Creek (Plm) | Canyon | 25,569 acres/10,348 hectares | Los Angeles & Ventura |

| Middle Sespe Creek (Sm) | Canyon | 24,246 acres/9,812 hectares | Ventura |

| Mint Canyon (MC) | Canyon | 4,877 acres/1,974 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Montalvo (Mon) | Valley | 7,316 acres/2,961 hectares | Ventura |

| Mount Piños (MP) | Mountain | 66,953 acres/27,095 hectares | Ventura & Kern |

| Nordhoff Ridge (NR) | Mountain | 40,972 acres/16,581 hectares | Ventura |

| Ortega Hill (OH) | Mountain | 24,974 acres/10,107 hectares | Ventura |

| Oxnard Plain (OP) | Plain | 88,058 acres/35,637 hectares | Ventura |

| Parker Mountain (ParkM) | Mountain | 22,208 acres/8,987 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Peace Valley (PV) | Valley | 22,748 acres/9,206 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Pine Mountain Ridge (PM) | Mountain | 112,031 acres/45,338 hectares | Ventura |

| Pollard Point (PP) | Mountain | 2,218 acres/898 hectares | Ventura |

| Portal Ridge (PR) | Mountain | 58,969 acres/23,864 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Red Mountain (RedM) | Mountain | 26,342 acres/10,660 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Redrock Mountain (RRM) | Mountain | 9,766 acres/3,952 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Ridge Route Ridge (RRR) | Mountain | 14,187 acres/5,741 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Rose Valley (RV) | Valley | 2,611 acres/1,057 hectares | Ventura |

| Saddleback Mountain (SadM) | Mountain | 15,360 acres/6,216 hectares | Los Angeles |

| San Francisquito Canyon (SFC) | Canyon | 28,383 acres/11,486 hectares | Los Angeles |

| San Gabriel Mountains (SGabM) | Mountain | 109,073 acres/44,141 hectares | Los Angeles |

| San Guillermo Mountain (SGM) | Mountain | 25,427 acres/10,290 hectares | Ventura |

| Santa Clara River Valley (SCR) | Valley | 149,787 acres/60,618 hectares | Ventura & Los Angeles |

| Santa Paula Canyon (SPC) | Canyon | 8,971 acres/3,630 hectares | Ventura |

| Santa Paula Ridge (SPR) | Ridge | 30,996 acres/12,544 hectares | Ventura |

| Santa Susana Mountains (SSM) | Mountain Ridge | 167,689 acres/67,863 hectares | Ventura & Los Angeles |

| Sawmill Mountain (SawM) | Mountain | 65,953 acres/26,691 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Sierra Pelona (SP) | Mountain | 81,413 acres/32,947 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Sierra Pelona Valley (SPV) | Valley | 8,490 acres/3,436 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Soledad Canyon (SolC) | Canyon | 25,336 acres/10,253 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Sulphur Mountain (SM) | Mountain | 33,917 acres/13,726 hectares | Ventura |

| Tehachapi Mountains (TehM) | Mountain | 2,918 acres/1,181 hectares | Los Angeles & Kern |

| Topatopa Mountains (TM) | Mountain | 67,262 acres/27,220 hectares | Ventura |

| Upper Middle Piru Creek (Pum) | Canyon | 17,524 acres/7,092 hectares | Ventura & Los Angeles |

| Upper Piru Creek (Pu) | Canyon | 34,168 acres/13,828 hectares | Ventura |

| Upper Sespe Creek (Su) | Canyon | 11,208 acres/4,536 hectares | Ventura |

| Ventura Hills (VH) | Mountain | 57,421 acres/23,238 hectares | Ventura |

| Warm Springs Mountain (WSM) | Mountain | 17,296 acres/7,000 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Whitaker Peak (WP) | Mountain | 49,877 acres/20,185 hectares | Los Angeles |

| Whiteacre Peak Ridge (WPR) | Mountain | 91,321 acres/36,957 hectares | Ventura |

A summary of the flora, special-status plants, habitats, and recommendations for each of the bioregions is provided in the botanical resources report, which will be completed by the end of 2022 and published here.

The watershed is rugged and topographically diverse, with a flat coastal plain, low hills, broad valleys, deep canyons, and tall and rugged mountains. The geology consists of a range of igneous and sedimentary formations, some very very old.

Flora

The flora of the watershed is varied by basically typical for a Mediterranean climate. It consists of vascular and nonvascular plants. The vascular plants consist of trees, shrubs, forbs and herbs, and grasses and graminoids (grass-like plants that are not in the grass family). Nonvascular plants include bryophytes and lichens, both of which are quite different from each other and from vascular plants, except that they all photosynthesize.

Photos by David L. Magney

Vascular Plants

Vascular plants are by far the dominate plant form in the watershed, but in number and in size, even though we have some very small vascular plants.

As of the date this is published, we know that there are about 2,336 vascular plant taxa occurring in the watershed. We use the term “taxa” to designate the lowest taxonomic level, which could be a subspecies, variety, or form of a species. “Species” is the next highest level. So, to avoid confusion, we say there are X number of taxa rather than X number of species. If we stopped as the species level, we would be ignoring a large percentage of the flora.

There are many common and widespread plants in the watershed, such as Chamise (Adenostoma fasciculatum), which is a large shrub in the Rose family that is the most dominant shrub of the chaparral vegetation in California, and in the watershed.

At the other end of the spectrum, the rarest plant within the watershed had only one population in the entire world, and it is along the bank of the Santa Clara River, Newhall Sunflower (Helianthus inexpectatus), a large, sprawling perennial in the Sunflower family. It has a very restrictive habitat, a deep freshwater spring.

Of course, with 2,336 vascular plant taxa occurring in the watershed, you will see at a minimum 25 or more taxa in any one place you stand (or sit), as long as you are not in a colony of one species. Hike any trail and you will see closer to 100 different taxa.

Keep in mind that the plant you actually see will depend on the season you are in. Since a large part of the flora consists of annuals and geophytes (perennials that emerge each year from underground structures such as bulbs, tubers, or corms), you might miss many if you are there in the summer, fall, or early winter. But return in the spring and what a surprise you will have. Below are some photos of just a few taxa that occur in the watershed.

Left: Amsinckia menziesii (Common Fiddleneck), an spring annual. Right: Bloomeria crocea var. crocea (Golden Stars), a bulb.

Left: Collinsia heterophylla (Chinese Houses), a spring annual. Right: Calochortus plummerae (Plummer’s Mariposa Lily), a bulb.

Left: Chloropyron maritimum ssp. maritimum (Salt Marsh Birds-beak), a summer-flowering wetland annual. Right: Chorizanthe staticoides (Turkish Rugging), a spring annual.

Bryophytes

Bryophytes include mosses, liverworts, and hornworts. They are basically “leafy” plants that lack vascular structures such as stems, twigs, trunks, roots, etc. and the leaves are usually just one cell thick.

We don’t know how many species of bryophytes occur in the watershed because no bryologist has yet conducted a floristic survey of the watershed for this group of plants, but we are working on it. There are likely about 100 bryophyte taxa in the watershed. For example, there are 98 bryophyte taxa known for all of Ventura County. Below are two examples of mosses from Ventura County, Homalothecium arenarium on the left and Bestia longipes on the right. Both grow in shaded areas on cliff faces and soil.

Bryophytes grow on rocks, soil, and bark. Some prefer moist sites and others can survive in arid sites, such as on boulders and rock faces in full sun. A microscope is generally required to identify many of the bryophyte species, but some are easy to recognize after you become familiar with them, at least to the genus level. Such is the case for the genus Grimmia, which often forms very dense rounded tufts attached to rocks.

Left and right: Grimmia on a rock outcrop and a close-up of the tuft. This was found on a steep north-facing slope just above Lockwood Creek at the east end of Lockwood Valley in northern Ventura County.

Just like the vascular plants, we have very common and widespread bryophyte taxa and some that are very rare.

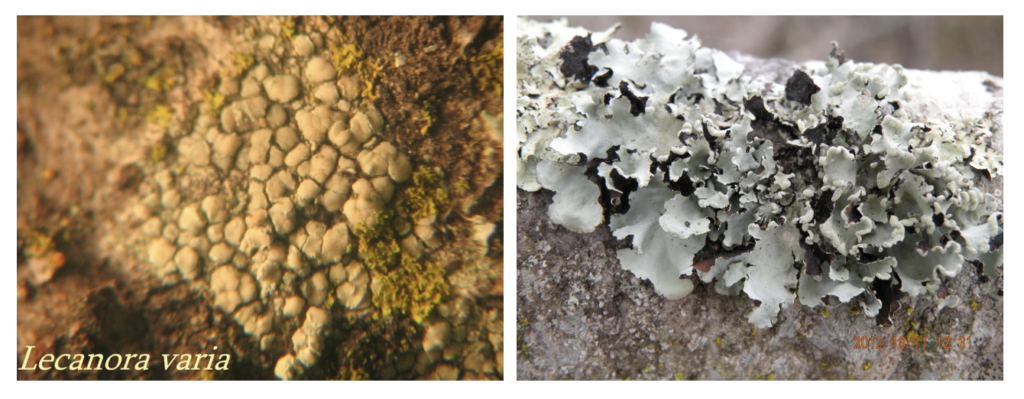

Lichens

Lichen are entirely unique type of plant, consisting of at least two very different species, a fungus, and one or more algae or cyanobacteria species. The algae photosynthesize, providing food for everyone, while the fungal component provides shelter and nutrients.

The part we generally see is the thallus, which is somewhat leaf-like. Lichens have three basic lifeforms: crustose, foliose, and fruticose. Crustose lichens are like crusts on rocks, soil, and bark, often tightly attached to the substrate. Foliose lichens are leaf-like, usually with only a part of the thallus attached to the substrate. And the fruticose lichens are those that simply or intricately branched. Some fruticose lichens are used to represent shrubs and trees in model displays, such as by hobbyist model train enthusiasts.

Left: a crustose lichen (Lecanora varia). Right: a foliose lichen (Physcia).

Left: a foliose lichen with brightly colored apothecia (the reproductive part) (Teloschites). Right: a fruticose lichen (Ramalina).

Lichens are also poorly surveyed in the watershed, or anywhere else for that matter, mostly because there are very few lichenologists. We estimate that there are around 400 species of lichens in the watershed.

Visit the California Lichen Society website for a lot more information about lichens.

Vegetation/Plant Communities

Vegetation is the general term for a bunch of plants growing in the same area or habitat. We often call them plant communities. One thing to keep in mind, plant communities are made up of a number of plants that like to grow in the same conditions, so there can be lots of overlap by specific species.

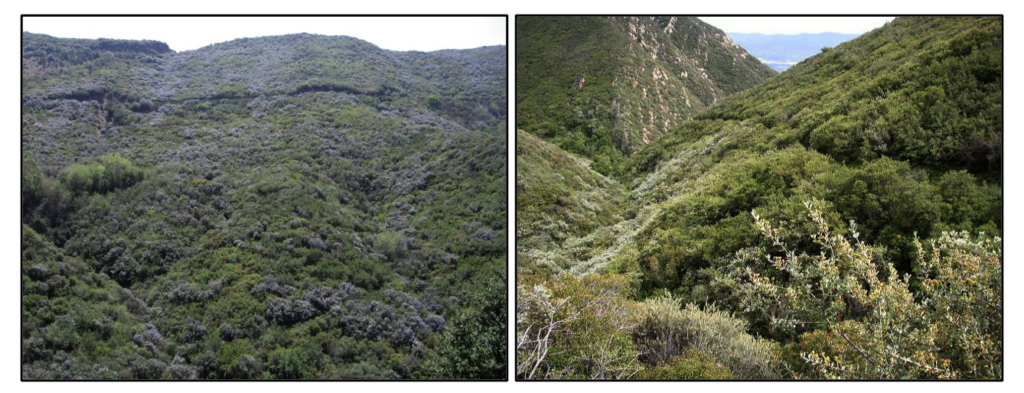

Chaparral is a common shrubland form of vegetation dominated by large shrubs, such as Chamise. Other genera that make up our chaparral includes: Arctostaphylos (manzanitas), Ceanothus, Prunus, and Frangula (Coffeeberry). There are several species of each of these genera found in the watershed. Chaparral alliances are truly the dominant vegetation forms in the watershed, occurring on most hill and mountain slopes.

Two examples of chaparral dominated by Chamise and Ceanothus species.

Coastal Sage Scrub is a common but impacted shrubland form dominated by drought-deciduous and aromatic shrubs of lower stature (height) compared to chaparral. The dominant and characteristic genera of Coastal Sage Scrub alliances includes Artemisia (Sagebrush) and Salvia (Sages), with of course, many other genera and species. Coastal Sage Scrub communities are most common on the slopes of the lower hills and mountains, closer to the coast.

Coastal Sage Scrub dominated by California Sagebrush (Artemisia californica) and Purple Sage (Salvia leucophylla).

Oak Woodland is another, dominated by one or more species of oak (Quercus). The lower valleys are dominated by Coast Live Oak (Quercus agrifolia) and our mountain canyons and slope have Canyon Live Oak (Q. chrysolepis) and Interior Live Oak (Q. wislizenii).

Forest vegetation in the watershed is typically associated with the Mixed Conifer or Yellow Pine Forest on the higher mountains of the watershed. The most common and abundant conifer forest trees within the watershed are Jeffrey Pine (Pinus jeffreyi) and Singleleaf Pinyon Pine (Pinus monophylla). Jeffrey Pine occurs on the highest mountains. Singleleaf Pinyon Pine dominates the drier, somewhat lower mountain slopes.

While the vegetation of the watershed has yet to be mapped and fully classified, we expect there to be over 100 different vegetation alliances, and many more plant associations. Some of those will be rarely found.

Core Challenges

It is nearly impossible to find all the populations of rare plants in such a large area, especially one as rugged at the Utom watershed. And every year we find taxa within the watershed that had not been documented within it before. So a botanist’s work is never done, or a flora is never complete. As soon as we publish a flora, someone finds something new for the flora.

Protecting the botanical resources from inappropriate land uses is a big challenge. All of our cities are expanding outward when they should grow up, not out. The changes coming in our climate is an big unknown threat. Some species will simply not be able to survive the changes in the local climate, and plant migration to better growing conditions is often blocked by human land uses, such as pavement and buildings, or agricultural fields (which of course we need to survive).

Keeping our open spaces free of trash from littering along watershed roads and trails is a routine problem from uncaring humans. Distilling an environmental ethic in all citizens is extremely important to protecting our environment.

Setting aside large enough tracts of land for our flora, scattered throughout the watershed, is necessary to conserve the flora. Educating our elected leaders and bureaucrats is necessary to make sure they understand the importance of the flora and what is necessary to protect this resource.

Watershed Plant Discovery Program

Since the search of the flora is never done, CNPS is establishing a watershed plant discovery program. This program will include hikes by CNPS chapter representatives, seasonal surveys of unbotanized areas of the watershed, and tools for interested citizens to help document the flora, and monitor the condition of rare plant populations (through our Rare Plant Treasure Hunt program).

Three CNPS chapters survey portions of the watershed, the Channel Islands Chapter for the Ventura County portion, and the Los Angeles/Santa Monica Mountains and San Gabriel Mountains Chapter for the Los Angeles County portion. Visit the chapter websites for more information and how you can participate.

Tools such as Calflora.org collector and iNaturalist are easy to use applications that anyone can use to document the occurrence of a plant (or animal).